Only in the realm of paper money could a 19th-century ventriloquist leave behind a legacy that continues to be valued and enjoyed by currency collectors over 150 years after his death.

Nicolas Marie Alexandre Vattemare (called Alexandre by his friends) was born in Paris in 1796. At an early age, he discovered he had a talent for ventriloquism and the ability to imitate sounds. He later trained as a surgeon but was denied a diploma because he used his ventriloquist skills to make cadavers appear to speak during surgical exercises. After that temporary setback, Vattemare was assigned to care for several hundred Prussian prisoners of war afflicted with typhus in 1814 during the Napoleonic Wars. He accompanied them to Berlin, where he embarked on a professional career as a ventriloquist.

Successful Performer

Between 1815 and 1835, Vattemare performed in over 550 cities under the stage name “Monsieur Alexandre.” His audiences included the czar of Russia and other royalty. He did not use a ventriloquist’s dummy, but rather presented plays in which he portrayed all the characters using different voices. He wrote all the material himself and performed in French, German, and English. By 1835 he was both famous and financially secure. He then retired from show business to pursue philanthropic interests.

Vattemare’s passions were free public libraries and the sharing of culture. In his travels, he accumulated large collections of books, coins, engravings, and other items. In his visits to museums and libraries, he discovered a high degree of duplication in their collections and promoted his system of cultural exchanges between institutions.

American Legacy

Government bureaucrats in France were not receptive to his system. Vattemare visited the United States in 1839-41 and 1847-50. His system of exchanges was more positively received during these trips. In 1848 the U.S. Congress gave him $5,940 a year to support his programs. He is credited with founding the Boston Public Library and the American Library in Paris. He was also a major contributor to the Smithsonian Institution, which adopted a cultural exchange program based on Vattemare’s concepts. By 1853 over 130 libraries around the world were part of the cultural exchange program that he

had envisioned.

After Vattemare died in 1864, his exchange program ran out of money and soon collapsed. But he charted the path for a general expansion of the library system in the United States and creation of cultural exchange programs that have stood the test of time.

Bank Note Collection

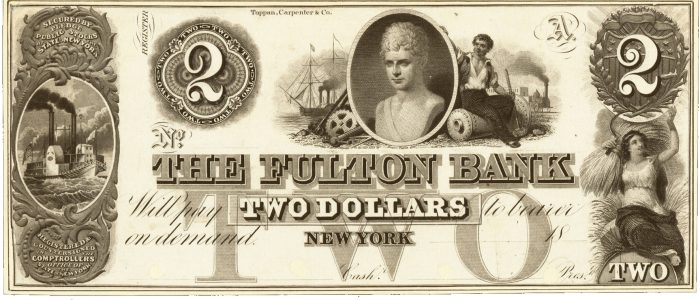

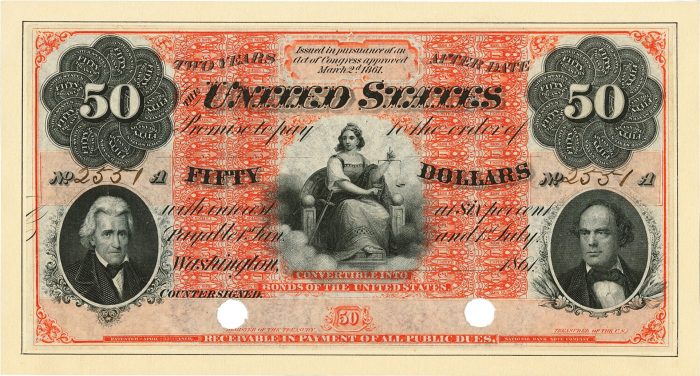

As part of his activities in the United States between 1837 and 1850, Vattemare assembled a collection of paper currency that he intended to donate to a library in Paris. This assemblage comprised American bank notes and other financial instruments. On his trips to the United States, Vattemare established personal contacts that allowed him to obtain U.S. Federal bonds and notes from predecessor firms of the American Bank Note Company (Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Co., and others) and the New York State Comptroller’s Office. (He obtained obsolete bank note proofs from the latter.) He later obtained federal items from the United States Consul General offices in France and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. Altogether, Vattemare filled four albums. Each note or bond was carefully rim mounted on the back, creating a frame-like appearance. This allowed both sides of a note to be viewed. Another feature of nearly every Vattemare Collection example is a thin black border drawn by hand on the front of each note. These two distinctive hallmarks are key ways to attribute items to Vattemare albums. These albums were sold in 1980-81 by Vattemare’s descendants. The collection was broken up, and occasional examples still appear on the market today.

So, if you see a nice early proof bank note or Federal debt instrument with what looks like a frame around the perimeter of the back and a simple black ink border around the front, there’s a good chance you’re looking at a neat piece of 19th-century international numismatic history. It was likely owned by a one-time ventriloquist who made dead bodies talk in his precocious early medical school years! As the saying goes, “You can’t make this stuff up!”

A version of this article appears in the March 2024 issue of The Numismatist (money.org).